- Find a Doctor

-

Services

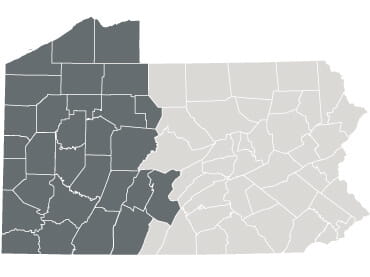

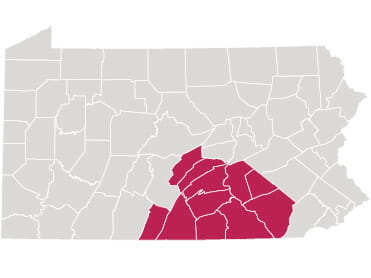

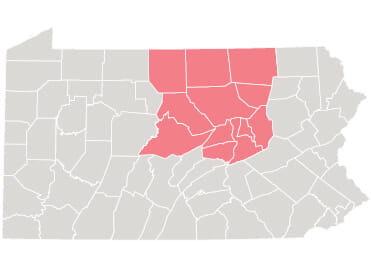

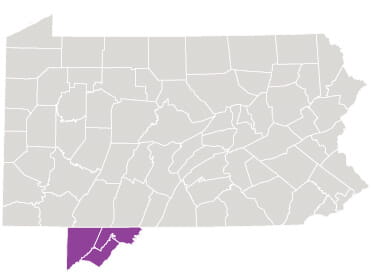

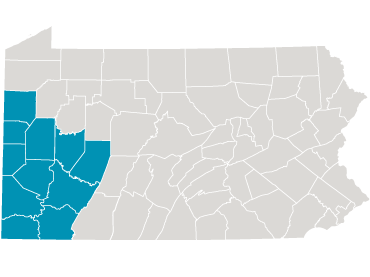

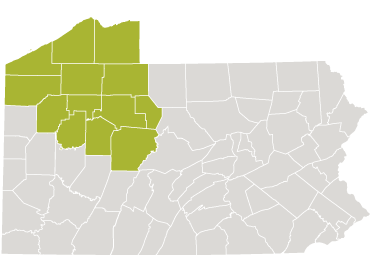

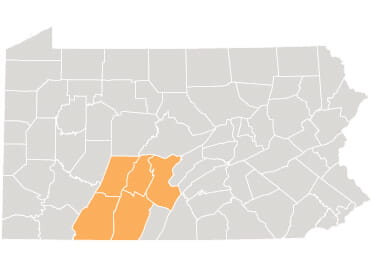

- Services by Region

- Frequently Searched Services

- See All Services

Find a UPMC health care facility close to you quickly by browsing by region.Frequently Searched ServicesAllergy & Immunology Behavioral & Mental Health Cancer Ear, Nose & Throat Endocrinology Gastroenterology Heart & Vascular Imaging Neurosciences Orthopaedics -

Locations

-

Patients & Visitors

- Patient Portals

ALERT:

Starting Feb. 29, masking is optional but encouraged in UPMC medical facilities and most patient care settings.